Basslines

Filling in the Blanks Part 1: Bass Lines

First considerations

Many of us who have been in bands remember quite clearly the clichés associated with each member. You know the sort of thing; the singer is a rampant egotist (and usually a little thick), the guitarist is always trying to hog the limelight and secretly hates the singer, the drummer is simply a moron who hits things, and the bass player? He’s the strange one, the quiet one at the back who seems quite normal until you get to know him and you realize that he’s the one with the bizarre habits, the rampant misandrist and harbours a secret wish to kill the guitarist and take over as singer. Despite this, everyone who has been in a band knows that the right bass player will make a good band great, and a bad bass player is a terrible pain in the neck.

As the bassist is the player who is carrying the whole can for harmony, chord sequence and instrumental interest, you’d better make sure he’s up to the job!

For those of us who don’t play in bands but instead create our arrangement masterpieces by pushing a mouse pointer around a screen, we have chosen to be everyone in the band bar the vocalist. Therefore, we’d better make sure our bass lines are excellent.

Here’s how…

Root Work

In popular music, you tend to find that the bass line follows the root note of the current chord being played. Here’s a simple example:

Chord Sequence:

C Dm F G

Bass note played:

C D F G

This really couldn’t be simpler, but why is it that this feels natural, complete and comfortable? Let’s take a little look at our old friend, the C chord again:

As we can see, this chord is made up of three notes, ‘C’, ‘E’ and ‘G’, but the most important note by far is the root note ‘C”. Even though the ‘C’ note is the first note on which all the rest are built, it also completes the chord, making it feel whole. Without it, we could be playing the first two notes of the chord Em, which is quite different.

Now take a look at the keyboard when we add another note ‘C’, this time a whole octave lower:

This note appears to ‘double up’ on the ‘C’ in the chord, and in fact that’s exactly what it does. It reinforces the strength of the root note in the chord, making the whole chord sound far more powerful, purposeful and strong. You’ll soon find that if you get into the habit of playing chords on your keyboard with a simple bass note doubling the root note an octave lower, when you stop playing the bass note the whole sound of the chord feels weaker.

Surprisingly, when you’re playing these four note chords it’s quite possible to leave out the original root note (see below) and still have the sound of a complete chord. Try playing this:

You’ll notice that the chord sounds complete, but quite ‘open’. Light, but still purposeful. We still have all the notes required for the C chord, even without the original ‘C’ note.

This is straight forward, but I can tell you’re itching to get technical…

So why does simply playing the root note an octave lower sound so full, natural and powerful? Well, in simple terms, you’re directly reinforcing the chords that already exist in the song. You’re adding extra sonic energy at a lower frequency that does not interfere with the other frequencies in the chord, it only adds to them. If you played any note other than “C’, you would be complicating the sound of the chord and so would lose a certain amount of power. We’ll talk about that a little later on…

We don’t have the space here to fully discuss psychoacoustics, but for some reason human beings feel quite comfortable with low frequencies that we understand and can identify, it helps us to feel ‘grounded’, safe, and a whole load of other feelings associated with our security. Next time you’re listening to your favourite song at home, try turning the bass on your stereo right down as far as it can go; don’t you instantly feel slightly anxious, just itching to put the bass back in?

In contrast, try turning the treble all the way down. It doesn’t sound great, but you don’t get that anxious feeling to anything like the same degree. Amazing.

Getting a little clever

Following the chord sequence of your song directly, just playing root notes as you bass line is perfectly acceptable. Listen to any Trance music, any Punk music and you‘ll find that the whole bass line in these styles is simply a rhythmical pulsing of the root note of the current chord. And it feels perfectly natural, strong and most importantly loud.

Here are some examples of songs whose bass lines follow the root note of the chord:

Artist Song

Eamon Fuck It

Fatboy Slim Rockafeller Skank

Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit

Sex Pistols Anarchy in the UK

Using notes other than the root note

But we don’t have to use the root note of the chord. There are actually plenty of occasions where it’s better if we don’t. Here’s an example

Staying on one note when the chords change

This technique used to be known as a ‘pedal bass’, probably as a reference to the bass pedals you have on a cathedral organ. The principle is simply that you play one bass note (or pitch in this case) whilst the chords of the song change above it. Try playing this:

Chords:

C F Amin G

Bass Note:

C F A G

So far so good. This time, try playing the note throughout the chord sequence, as below:

Chords:

C F Amin G

Bass Note:

C C C C

You’ll notice that having the bass note staying the same throughout our sequence alters the feel of it dramatically. The sequence now feels like its moving less. It also feels a little more sophisticated, jazzy, especially when we play the G chord at the end. There is a specific reason for this, take a look at the notes used in the chords:

C Major

F Major

A Minor

G Major

You’ll notice that the note ‘C’ appears in all of these chords except G. It is the fundamental in C, the fifth in F and the third in Am, but does not appear in G at all. That is the main reason why it feels slightly jazzy to have ‘C’ as a bass note under G, when it feels quite natural with the other chords.

But, despite not being in the chord of G, the ‘C’ bass note still feels good, it has quite a different feel than playing ‘G’ and certainly sounds interesting without complicating things too much. Again, we have a nice instance of tension and release, where the G chord naturally leads us back to the C chord which is reinforced by the pedal note ‘C’ not being part of the G chord.

There is much more we can discuss about this technique, so we will return to it later in the course when we are discussing ‘pad’ sounds and extended chords. In the mean time, here is a couple of famous tunes that use this technique:

Frankie, they couldn’t be bothered with bass lines

Artist Song

Eminem Lose Yourself

Frankie Goes to Hollywood Relax

Using bass notes that don’t appear in the chord???

This can be an interesting way of spicing up a chord sequence, but a word of warning! This technique only really works when used sparingly, and if you’re working in the dance music field then I would say that unless you’re using a passing note in a bass riff, or maybe using a pedal bass, they are best avoided.

But this is not a hard and fast rule, plenty of great songs use bass notes that don’t appear in the chord. We’ll return to this subject later in the course when we discuss extended chords.

We got rhythm

Let’s take a quick look at rhythm in our bass lines. So far, every bass line we’ve considered has been a ‘pedal’, a drone or just simple pulse that just underpins the chord we’re using. That’s all very well and certainly useful but there’s so much more that a bass line can do…

The rhythm of a bass line can be as simple or as complicated as you require, but there are some basic principles that you should stick to. Essentially, your bass line should either move with, or directly compliment, the kick drum pattern in your song. Let’s consider the complimenting approach first:

Robert Miles, real name Roberto Milano. He’s Italian by the way

‘Children’ by Robert Miles

This tune has a classic example of a bass line complimenting the kick drum pattern; in fact it’s hard to imagine a bass line that’s simpler than this. The pitch of the bass is the root note of the chord in use, and it’s a simple pulse in exactly the same rhythm as the kick drum. But, to get maximum clarity from the bass note and to avoid interfering with the sound of the kick drum (as they occupy very similar frequencies in the sonic spectrum), the bass pulse happens on every offbeat.

This has the effect of reinforcing the ‘push-pull’ feel of the house beat. If you nod your head in time to the beat in this tune you’ll find that your head is fully up when the bass note sounds…this feels quite exciting and certainly makes dancing to this rhythm very easy. This bass line rhythm has been used in Trance music for more than a decade as it is so effective.

Here’s a variation on this theme:

FRANZ FERDINAND, successful Glaswegians.

“Truck Stop” by Franz Ferdinand

Again, the bass line follows the chord sequence closely, but this time it bounces between two octaves, with the clearer higher octave root note sounding on the off beat, much like the Robert Miles track. This kind of bass line was particularly popular in the late 1970s and early 1980s and is experiencing a revival right now.

It’s my contention that it was so popular 30 years ago because it’s an extremely easy bass line to play, just rocking between two notes on keyboard. Try it when you get a chance. Speaking of rocking…

Let’s move…

So far, the rhythms we’ve been considering do not sound with the kick drum, in fact they specifically avoid the kick drum so that there is plenty of ‘sonic room’ so the bass note can be heard clearly in the arrangement. But, these bass lines tend to be the exception rather than the rule. Most bass lines move with the kick drum, sometimes sounding at the same time. Both the bass instrument and the kick drum are following the same rhythm, although they don’t have to sound at the same time all the time. This has the effect of reinforcing the kick drum with an easily identifiable pitch, strengthening both the sense of rhythm and of harmony.

“What the World means to U” by Cameron

Notice that the bass line feels rock solid. The fact that the bass line is largely locked in with the kick drum creates a very well defined groove, which feels very exciting and is ideal for dancing to. Here’s another example of the same thing:

“C’mon” by Mario

Another rock solid bass line. This track has a very busy vocal arrangement; Mario hardly seems to pause for breath.

“One Horse Town’ by the Thrills

Ok, quite a different style to the Cameron track but the principle is the same. The bass notes and kick drum hits largely sound

at the same time, creating a solid groove. Also notice that the bass line is often reinforced by a sampled piano sound, helping to define its pitch and rhythm. Lastly, notice that the bass note sometimes stays on one pitch whilst the chord changes above it.

That covers a very large number of the typical bass lines that you’ll find in pop music. But so far we’ve only really considered bass lines that just reinforce either the rhythm of a track of the harmony, sometimes both. There are plenty of instances where bass lines do a bit more work than that….

What’s a riff?

A riff is a short musical phrase, usually quite rhythmical, that is played repeatedly to help create a groove.

As far as our bass lines are concerned, a bass riff is a short, hooky phrase that supports the chords used in our songs. Let’s take an example:

“In Da Club” by 50 Cent

We’re already quite familiar with this tune, but lets concentrate on the bass line for now. It consists of a very simple repeated phrase. This phrase is hooky and is reinforced by the higher string line at various times in the song. Notice that the bass line follows the kick drum exactly, also that the sound used is quite dull i.e. is not bright, contains few high frequencies.

This bass riff has one other fascinating attribute: it does not play the root note of the chord until the very end of the section. This is very unusual, and heightens the sense of tension in the whole track very effectively.

“Insane in the Brain” by Cypress Hill

Again, a repeated phrase played on quite a dull sounding instrument (which could be an acoustic bass). Notice again that the bass line and the kick drum are locked together. As is typical in Hip Hop, the bass line is the only part that is carrying any real harmony i.e. there is no sequence of chords, no other parts playing a melody or a riff etc.

Dub reggae. Notice, just like in Hip Hop, that the bass line is almost the only instrument playing any kind of ‘tune’. The bass line follows the chords being used, and plays a repeated phrase that moves the track along, again creating a groove that hypnotises the listener.

Heavy rock, and one of the most familiar riffs ever. You may know this tune as the theme to Top Of The Pops. Its hooky, loud, brilliantly well played. Enough said.

Who (or what) will play my bass line?

From the 1950s until the 1980s the electric bass guitar has been the instrument of choice for playing bass lines. Up to this time, bass lines were usually played by the upright or acoustic bass, a kind of oversized ‘cello which was normally plucked by the player.

The electric bass guitar has many advantages over the upright bass: it’s much lighter, making it easier to transport. It’s much smaller and tougher, and therefore less prone to damage in transit. Being an amplified electric instrument, it can be far louder than an upright bass. And its sound is fuller, deeper and brighter, which makes it far more versatile than its predecessor.

In rock music, the bass guitar always plays the bass line. In fact, whenever a band plays you’ll find there is a bass guitarist.

But what about if we’re not playing in a band? What about if we’re programming our arrangement using MIDI equipment, samplers and software synthesizers?

In that case, just about anything goes. You can use any sound that you have available to play your bass line, so be creative! Here’s a selection of sounds that you may often hear playing the bass line in pop music:

- Pizzicato (plucked) strings. “In Da Club” springs to mind

- Hammond Organ. Very popular in house and garage styles. An original B3 organ is an unwieldy beast, and very expensive, so you could use samples instead, or one of the many software instruments that emulate the sound of a Hammond.

- Sampled Bass Guitar. Why use a sampled bass when you could just play one? Well, sampled bass guitar sounds much more rigid and precise than a played bass and can also be affected so it sounds very percussive. Listen to Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Two Tribes” for an example of this.

- TR808 kick drum. Eh? A kick drum playing a bass line? Oh yes, in fact this sound formed the basis of many jungle/drum ‘n bass sounds in the 1990s. You sample it, map it across the keyboard so the pitch of the drum changes just like a sample of a voice would do and voilá, instant sub bass!

- Synth sounds. Some vintage synthesizers sound great as bass instruments. Here are some of my favourites:

Minimoog

The most ‘sought after’ synth of them all. It excels at huge, warm ‘phat’ bass sounds. Can be heard on many tracks from the 1970s through to the present day, including songs by Stevie Wonder, Gary Numan, Motiv8, Chemical Brothers, and Artful Dodger amongst many many others.

Roland TB303

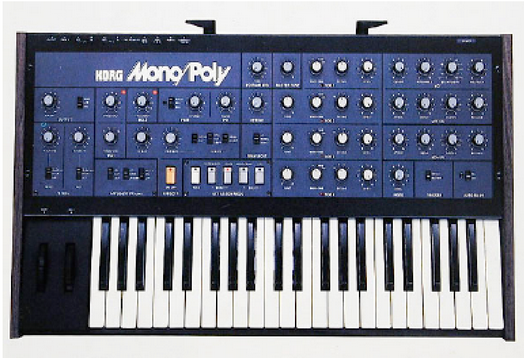

Korg Mono/Poly

My personal favourite. Korg synths are not really known for being great bass instruments, but this one is an exception. It has four oscillators, which enables it to make huge, rich and dense bass sounds that can dominate a whole track if you so desire. Quite hard to find these days, sadly.

Roland Juno 106

But what should my bass sound sound like?

There really are no rules about bass sounds, but I’ve prepared some guidelines for you. Stick to these and you’ll avoid some very common problems:

- Use a simple sound. You really don’t need a sound that evolves and changes massively through time. You tend to find that synth manufacturers fill up the preset banks on their machine with very impressive patches that sometimes can sound like completed records when you hold down just one key. Avoid these like the plague. They sound great in a shop but sound terrible in a track.

- When making dance music, use a sound with a quick attack time. By this we mean an attack or rise time of less than around 200ms. Don’t forget, your bass line is as much a rhythmical part as a harmony part, so let your sounds be punchy, not flabby!

- Don’t use stereo bass sounds, nor use stereo effects on bass parts, unless you absolutely know what you’re doing. First of all, the human ear is not very sensitive to stereo imaging at low frequencies, so there’s not much point in sweeping your bass sound from speaker to speaker. Speaking of speakers (as it were), you really need both speakers to be outputting exactly the same sound at exactly the same time in order to be able hear what the bass line in doing. In other words, the bass line must be in phase, something it definitely won’t be if you’re using a stereo bass sound. So don’t.

- Avoid bass sounds with a large amount of mid/high frequency content. Most of the time you want your bass to occupy a very tight frequency range in your mix, so that it does not interfere with other parts in your arrangement. You’ll notice that in most dance music, the bass sounds are very dull. Contrary to what you might expect, this means that they sound powerful, and move in a controlled way. Its rare that you find a bright bass sound, except perhaps in the style known as Electroclash.

- Keep your bass lines monophonic, unless you absolutely know what you are doing. Nothing can blur a bass line more easily than notes overlapping, so please make sure that either your synth is set so that it can only play one note at a time, or that the release on your envelope generator is set to very short i.e. less than 50ms. Having said that, some arrangers and producers make a virtue out of playing chords in their bass lines. Check out “Pure Shores” by All Saints/William Orbit for a bass line playing fifths through the verse (on a Juno 106, naturally). But be aware; this technique is used very rarely and always carefully.

How Low Can You Go?

Beginners making dance music of all kinds seem to have an obsession with ‘sub bass’. They labour under the false impression that the lower you go in pitch with your bass sound the more powerful it becomes. However, unless you know what you are doing, this can be a fatal mistake for two reasons:

- The human ear’s sensitivity to pitch drops off quite sharply below approximately 40 Hz. What this means for musicians is that if you play your bass line lower than 40hz, the audience will hear a bass sound but they wont recognize it as a pitch, therefore it won’t be contributing to the harmony of your track. This could mean that your track lacks power, one of the things you were trying achieve by playing a low bass line!

- Very low bass lines can make your track sound quiet! It’s a common mistake: you program in a bass line, possibly using a bass sound that’s very close to a sine wave. Because your monitor speaker’s frequency range doesn’t extend as deep as you think, you have to keep turning up the bass line so you can hear it. Eventually, the bass line is occupying a massive amount of the dynamic range of your track, but you can’t hear this because your monitors can’t play those deep frequencies. The end result? The whole track (except the stupidly loud bass line) will sound very quiet when played on a sound system that can play those low frequencies. Again, not what you wanted.

As a general rule, it is a good idea for your bass line not to go any lower in pitch than an electric bass guitar can play i.e. the second ‘E’ below middle ‘C’. This means that everyone will be able to her your bass line, whether they’re in a car, listening on their iPod, walking around a supermarket or dancing in a club. Leave frequencies below this for very deep kick drums and special effects. You’ll be saving yourself a lot of trouble in the long run.

Some tips for a healthy bass line:

- Sometimes your bass line can get lost in a mix, so make sure its nice and loud…

- But not too loud! Don’t forget that most of the time your audience really only cares about hearing the vocalist…

- Consequently, don’t make your bass line overly complicated. It will distract the listener and could become quite fatiguing.

- So, by all means use an interesting riff as your bass line but don’t attempt to take the lead with your bass part. That’s the classic problem with bad bass players; they play far too many notes because secretly they hate being bassists and want to be lead guitarists instead. These people get fired from bands.

- If you can’t get your bass sound sitting comfortably in the mix, it could be that there’s too much going on in your arrangement. Take another look at your other parts and see if there’s any that you can lose. If you’re sure that there’s nothing you can afford to lose, try changing your bass sound.

- Don’t forget that your bass line is a musical part, so even if your only programming it in, try to imagine that you are physically playing a bass guitar or a keyboard through the song…if you can do this, you’ll find that your bass line will flow more naturally and not feel ‘programmed’. Normally, most listeners prefer it that way.

- Please make sure your bass instrument is in tune! This is not the 1960s; most listeners these days are used to hearing records that are always 100% in tune, so yours must be too.

- Also, please make sure that if you are playing (as opposed to programming) your bass instrument, or you have someone else playing it for you, that you get the timing of your bass line as tight as you can, synchronized closely with the rest of your rhythm parts. Nothing makes a song sound amateur and sloppy more than a bass player or drummer who isn’t playing in time.

One last thought…

You don’t have to have a bass line, it’s not mandatory. Leaving out a bass part can be very effective, and certainly is a bold move. Prince made several hit records without bass parts. “Kiss” and “When Doves Cry” are two of the most famous…