Music Composition – Intro

Introduction:

Welcome to Point Blank’s hit writing course, your introduction to success in the music industry. At the end of each session you will be given a set of course notes which expands on the subjects discussed during the day, and allows you to listen and participate during the session rather than spend your time writing your own notes (you can do that as well if you want). Included at the back of most handouts is a ‘Definitions’ sheet which explains new terms that you may not be familiar with. We hope you enjoy the course.

What is a Song?

Why should we bother writing Songs?

What does a song mean to us, the people who write them?

- Writing songs is fun

- Writing songs can be therapeutic

- You can earn a living writing songs

- Write a good song and you can become a millionaire

- Write a great song and it could be sung across the world for decades

On the other hand:

- There are more bad songs than good songs

- Most people dislike most songs

- Writing songs can be frustrating and time consuming

- Bands split over who writes the songs

- ‘With every hit, there’s a writ’…successful songs mean trouble!

Overall, writing a song is one of the most rewarding things a musician can do; it makes you feel happy, confident, attractive and can earn you a pile of cash too! Writing a song can be for simple personal pleasure, for a gig you are playing later that night, for an advert you’ve been asked to contribute to, a theme tune for a film, even a ringtone for a mobile phone. The opportunities are endless.

Who writes songs?

Alternatively, some acts write together. This tends to occur in rehearsals, where the band jam together, eventually leading to a completed song. In these cases, each player has usually not only composed what she plays on her own instrument, but has made a contribution to the writing of the song as a whole.

And then, there are hit writers who are not members of any band. These people write songs for other artists to perform. Burt Bacharach (Aretha Franklin, Dionne Warwick etc), Cathy Dennis (Kylie Minogue, Rachel Stevens etc) are good examples of these kinds of writers.

Whatever king of hit writer you intend to be, there are some important principles that apply to you and your forthcoming career. These form the basis of the way the music industry works with compositions. Luckily for us, it’s almost entirely good news.

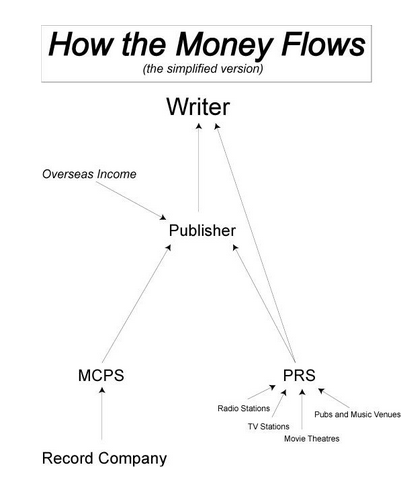

Let’s talk about money

What is copyright?

At this point, you may be thinking ‘Hang on, I’ve heard loads of stories of songwriters being ripped off and I’m terrified of it happening to me. Shouldn’t I be at least a little secretive about my work?’ Some of these stories may be true, but we’re saying don’t worry about this sort of thing at this stage. Please put any thought of protecting your copyright in these ways out of your mind for the moment. The truth is that you are highly unlikely to be ripped-off, and being paranoid about it could hold back your progress, possibly by years. Relax.

How do you divide the money (and the credit)?

So, you’ve written a song. It’s the best thing since the invention of the CD; now you have a real dilemma. No-one will hear the song until it’s performed, so you have to take it to your band to play. Thing is, they’re all a bit sensitive to the fact that you may be ‘hogging the limelight’ by seeking all the credit for the song, and want to make sure they get some of the glory too. What should you do? What have successful hit writers done through the years?

When they first did their publishing agreement as part of NEMS Enterprises they did write most of their songs together (although even early examples such as ‘I Saw Her Standing There’ might be written almost entirely by McCartney with just a couple of crucial lines by Lennon).

Fine, but what about my act?

Most often, bands agree between themselves what the song writing credits on their records will be well in advance of a record coming out, and may have a totally different agreement on how to divide the royalties from those songs that the public never sees. Traditionally, it has been considered that the top line is worth 50% of a song, and the track is worth 50%. Let’s take a fictitious example:

I WANT TO LOVE YOU ALL NIGHT LONG BABY

By The Helplessly Optimistics

(Richard Connected/ Robbie Face/ Andrew Haircut/ Jamie Talent)

The first thing to notice here is that the band members are listed alphabetically. This is a sure-fire give away that the credit has been agreed in a way that nobody appears to be more important than anybody else. But creatively and financially, nothing could be further from the truth; Jamie Talent wrote the melody, the chord sequence and the entire lyric on his mum’s piano…it’s his song. So the song split was agreed thus:

Jamie Talent: 50%

Richard Connected: 16.6%

Robbie Face: 16.6%

Andrew Haircut: 16.6%

The band members agreed that they would share the song writing income together, so there would not be huge inequalities in income between the members; the most common reason a successful band splits up is over the money earned by the songs they play. Next time you hear of a band splitting over musical differences, take a quick look at the song writing credits. It will often give you a real insight into what is actually happening.

Why is it important that each member of the band earns money from the song?

Every time the band’s song is played on the radio, the songwriter gets paid for the use of her song. Every time the song is played live, she’ll be paid. She’ll be paid for every recording of her songs that’s sold. And of course, the jackpot situation is if an unheard of third party records her song and has a runaway international hit with it. We’ll come back to that last one at the end of the course. But all these things lead to one unavoidable fact:

The person who writes the songs in a band earns most of the money

Meanwhile, all the non-writing members of the band have to survive on record company advances, royalties, and performance fees from gigs, TV and radio appearances. Typically, this is a far smaller amount than the money earned from the songs, so the songwriters agree to pay the non-writing members a share of the earnings from the songs. This will go some way to keeping the non-writing members happy, and most often helps to keep a band together even when one member is driving a Ferrari and the others are travelling in a Transit Van.

Sadly, this inequality of income can bring bands into conflict, especially if there is more than one writer in the band. Each writer knows that having more of their own songs released will increase their share of the song writing income. It was often the case in the 1970s that on a hit single by an established band you would find that the B-side was an awful song written by the bassist or drummer, included simply to keep that member happy and bumping up her share of the profits. Not a great situation for quality control, but it means there are thousands of curiously awful B-sides out there in the world.

Noel Gallagher of Oasis wrote all of their most successful songs, and is worth millions of pounds.

B-side???

What if I’m writing for someone else?

You have a great song, it’s a potential number one, and by some unlikely twist of fate it’s about to be recorded and released by the biggest star of the year. Everyone is patting you on the back and reminding you how much they’ve helped you through the years. Then it dawns on you: this is too good to be true, surely I have to give away loads of my future earnings to someone, this is the music industry after all?

Well, on most occasions you won’t have share the money you earn with the artist at all, certainly, there is no legal imperative for you to do that. This is one of the beauties of writing for a third party. They need your hit song far more than you need that particular artist to record your song. You can always take it along to someone else; you’re in the driving seat so to speak. Congratulations!

There is one major thing to be aware of though: Quite often, the artist you are writing for will object to a line you have written and change it for the recording specifically so they can take a chunk of your earnings (and credit). There are countless examples of this through the decades, there is very little we can do about it. Also, inevitably there will be a publisher waiting in the wings, waiting to bribe you with a big advance so you will sign a contract with them. Don’t fret unduly, these are both good problems to have, and we’ll discuss how you should approach these situations throughout the course.

(Pink with Linda Perry, who wrote the international hit ‘Get the Party Started’ in 2002)

Some Contemporary Songs to Discuss

James Blunt: Beautiful: 2005

Song Style: US Male Singer Songwriter

Song attributes: Simple arrangement

Characterful vocal

Similar chord sequence throughout the song

Gentle, vulnerable lyric

Questions: Why is the swear word ‘fucking’ not included in the radio version of the song?

How does James unfold the simple story he’s telling?

Kanye West: Gold Digger: 2005

Song style: Modern US rap:

Song attributes: Vocal intro

Light hearted lyric full of ‘day to day’ references

Sparse and simple arrangement

Verse/chorus/verse/chorus structure

Questions: What does the lyric establish about the lead character (Kanye)?

What about the female characters?

Is this song sexist?

Art Brut: Good Weekend: 2005

Song style: UK Indie/Alternative:

Song attributes: Very short intro

Humorous lyric full of ‘day to day’ references

Sparse and ‘trashy’ arrangement

Verse/chorus/verse/chorus structure

Song ‘falls apart’ at the end

Questions: What does the lyric establish about the lead character?

Why use those ‘trashy’ sounds?

What impression is given by the ending?

Eamon: I Don’t Want You Back: 2004

Song style: Modern American RnB.

Song attributes: Repetitive Chord Sequence

Repetitive vocal melody

Sparse arrangement

Verse/Chorus/Verse/Chorus structure

Strong and potentially offensive lyric

Questions: Why is the song not called “Fuck you”?

How does the song sound fresh with all this repetition going on?

Keane: Somewhere Only We Know: 2004

Song Style: Modern UK pop

Song Attributes: Strong reflective lyric

Simple piano led arrangement

Relatively complex structure

Q Questions: The chorus in this song happens nearly two minutes into it. How does the song keep your interest until this point?

How does the melody in this song show off the strength of the singer?

Maroon 5: This Love: 2004

Song style: Modern US pop

Song attributes: RnB style drum part

Distinctive bass line

Distinctive Chord Sequence

Vocal ‘ad libs’ follow the bass line

Energy picks up in chorus

Questions: How does the chord sequence achieve the sense of tension and release?

How is the contrast between verse and chorus achieved?

How does the band achieve the merging of the chorus into the verse?

Definitions:

Advance (record company advance): Money paid as a lump sum by a publisher or record company to a writer or artist as an advance payment of royalties due on the sale or exploitation of songs or recordings. This money is recoupable, meaning that in normal circumstances the writer or artist will not be paid further money until the advance has been repaid. Almost every publishing deal will incorporate advances, usually payable on signing of a contract and meeting a minimum release commitment, typically the release of an album or certain number of songs where the signing writer has made a contribution to the writing.

Co-write: The act of two or more writers writing a song together.

Jam: The act of two or more musicians improvising music together.

Performance Fees: The money paid to a musician for performing at a gig, on the radio or a TV show etc.

Recoupable: In publishing and recording contracts, certain costs that are incurred by the publisher record company must be recovered by exploitation/sales before royalties are paid. These are known as recoupable costs, and typically include the cost of recording an album, half the cost of making a video and the costs associated with touring amongst countless others.

Ringtone: 21st Century Mobile Phones often include the ability to play pre-defined melodies and backing tracks and whole audio files as the sound the phone makes when a call is coming in. A songwriter is paid a predefined sum every time a phone user downloads her song to use in this way

Royalties: Money paid to a writer or artist from the exploitation or sale of songs or recordings. Royalties are typically paid when the recoupable costs incurred by the publisher or record company have been met, then the writer or artist will be paid a share of the money collected. A common share for a writer in a publishing agreement is 75% of monies collected, 15% is typical for a band in a record deal although both figures can vary enormously.

Song split: An agreement between several parties where the each has agreed how the income from the song is shared.

Track: In song-writing terms, this is the instrumental ‘backing’ to a song.

Top-line: The melody and lyric of a song i.e. the vocal part of a song. This can sometimes include raps and instrumental solos