Vocals

Editing Vocals

Vocals, particularly the lead vocal, are the main focus point in most tracks, and not surprisingly this is the area where we spend perhaps most of our time and attention during all the stages of production. When mixing, some engineers choose to start with vocals first, or drums and vocals; others prefer to build the backing track and add the vocals at a later stage. Vocals in popular music are usually divided into two categories: lead vocal and backing vocals (BVs). Their basic treatment is quite similar (i.e. EQ, comp and further processing), although their place in the mix is quite different.

The key to a great vocal sound is at the recording stage. Factors such as the environment (vocal booth), microphone, mic preamp, A/D converter, and of course a great singer are all components of the final result. Today we will discuss some of the aspects of mixing recorded vocals in the context of popular music. Ideally, when mixing you should have one master lead vocal on one track, and other vocal parts such as a double-track and harmonies on separate tracks. However, you might sometimes be given a song with multiple takes of the lead vocal and you will have to decide which one is the best.

(Multiple takes of vocal)

Comping Lead Vocal

Even great vocalists sing better on some takes than on others, so it is common practice to record the same vocal part several times and then compile (or ‘comp’) the best phrases together into the final take. This is easy to do in a typical DAW, as you can view the various takes on adjacent tracks, audition them, then separate out the phrases you wish to keep and move them to a new track. If you only cut in between phrases, your edits shouldn’t be audible, but if you have to edit during a continuous phrase, try to edit either just before a hard consonant or during a sustained sound such as ‘eeh or ‘aah’, using a short crossfade to hide the transition.

Comping Vocals

Creating a perfect comp takes a bit of practice though, as it usually involves a bit more than just putting few phrases together. The result we want to achieve is that it sounds natural, as if it was a one-take performance. If the singer had a bad day, you might have to look into comping words and even syllables sometimes.

With all that comping, be careful to keep the breathing in, as an ‘airless’ performance can sound very unnatural, to the point of becoming uncomfortable to listen to. However, if some breaths are too loud in level, you can turn them down as long as you don’t lose them altogether.

Sometimes you might have to use crossfades between some regions for a smoother transition.

If there is a considerable amount of background noise, you might need to use a noise gate so that the whole take is cleaner and free of noises in-between phrases and parts. Another method with a DAW is to cut out the gaps between phrases or sections, either manually or using software that has a dedicated feature for this application.

Tone Control

Occasionally a vocalist will naturally move in and out of the sweet spot of a microphone whilst recording, changing the tonality and volume of the vocal. If the distance from the mic between two phrases from two different takes is too great, it can make it hard to create a unified composite vocal. Vocal takes that sound thin and further away from the mic can be altered using a plug-in EQ. However, I tend to do it offline, writing the effect as a new audio file so that the whole take is more unified, before adding further processing. For example, add some gain at 150Hz with a wide bandwidth to compensate for the lack of proximity effect, before adding some volume if the take seems to fall away in the mix.

(This technique can help match the tonality and volume of each take to sound like one phrase.)

Microphone Modelling

Different mics have different sonic “signatures.” A lot of this involves the microphone’s distinctive frequency response, so mic modelling software or hardware analyses a reference microphone’s response (along with other selected characteristics), and applies this signature to your mic. This process works best when the modelling software analyzes your mic as well – so it knows exactly what type of compensation to apply – or if you have a mic that is recommended as a signal source for the modelling device.

So can you really turn a Radio Shack mic into a vintage tube Neumann? No way. Granted, it may sound more like a Neumann than it did before, but no one’s going to prefer it to the real thing. However, with a good source mic, and if you don’t stretch the model too far (for example, having one dynamic mic sound like a different dynamic mic will probably work out better than trying to make it sound like a small diaphragm condenser type), mic modelling can be a very useful tool.

The issues are the same with modelled guitar amps. Clearly, plugging a guitar directly into a board through a modelling preamp is not going to feel the same as playing through a guitar amp and cabinet. That’s not surprising, but what is surprising is just how close you can come, and how by the time the track plays back, few people can hear the difference between the real thing and the simulation.

Mic modelling isn’t a replacement for a good collection of mics, but it can take a good collection of mics further. Even if simulating other mics isn’t your main interest, the complex response curves created by applying mic modelling have uses in their own right.

I have also used this plug-in to compensate when the vocalist moves in/out of the mic’s sweet spot. Using the proximity parameters, I have sometimes found this effect useful for improving a bad recording, even if ever so slightly.

Pops

What we term ‘pops’ in vocal recordings are produced by the consonants P and B when sung or spoken into a microphone. Although you usually deal with them at the recording stage (via a popshield, hi-pass filter, etc.) there are times when it’s not enough. Here again I use a plug-in to process the file directly, using the audio editor to select the desired portion more accurately:

- Use an EQ plug-in with a high-pass filter.

- Select the popped area just before the tone of the word and set your EQ filter to roll off everything below 150Hz or so, before processing it. You might have to split it into two regions so you can crossfade for a smoother transition.

- If you still hear a pop, repeat the process but delve a little further into the word (beyond the pop), and redo the crossfades.

- Experiment with different frequencies and slopes on the high-pass filter to achieve the best results.

Before consolidating your vocal composite into one audio file, keep your original tracks, perhaps saving them as another arrangement — just in case you need to redo a fade or change a word, for example.

Pitch Correction

Now that you have created the best possible performance, that you should be all you need to do, but there are times where some tuning inaccuracies can still be present.

The vocal is the one element of a recording that can’t yet be emulated by a computer, but it’s increasingly encircled by a rapidly expanding pool of plug-in processors, among them tuning tools that are mainly designed to correct pitch inaccuracies. There has been a continuous debate about the use of pitch correction tools, both technical and ethical. DAWs have become synonymous with a quest for perfection that can leave music soulless. However, correction of pitch started before the use of DAWs. Using pitch shifters such as the Eventide H3000 was fairly common in the 80s and 90s, but the emergence of a device by Antares called ‘Auto-tune’ changed the approach in producing vocals quite radically.

It all started when Cher made us ‘Believe’. Extreme Auto- tune creates the yodelling we all came to love and then hate in the late 90s. Since then, every year sees the arrival of two or three new pitch correction tools, among the leaders are: Melodyne (the professional version is a standalone application that can do much more than simple pitch correction, and possibly a better job at that than Antares’ Auto-tune), Waves have released a one (it looks like an hybrid of the Auto-tune and Melodyne), the SoundToys ‘Pitch Doctor’, and TC Electronic’s ‘Intonator’. There are many more.

Autotune’s primary use is to correct tuning inaccuracies, but it has and still is used for more creative effects.

Pitch correction applications, such as the Logic Pro utility (pictured) could most usefully be thought of as a real-time time-stretching algorithm. You can manually highlight the notes that you want to hear and increase or decrease the response speed to suit your needs. A slower response time may sound more natural but be unable to cover the mistakes, whilst a faster response time will get rid of the pitch discrepancies at the cost of the naturalness of the voice. Using a fast response time will result in a synthetic, almost robotic quality, which will be very noticeable if not desired.

The Quest for Perfection

“Perfection is boring.” Geoff Foster, a veteran engineer at Air Lyndhurst, was recently quoted in print as saying. “To some degree, Cher’s got a lot to answer for… Sure, [Believe] was an extreme example and meant to be an effect, but the public bought it, literally.

“From a pop standpoint the public said, ‘We don’t care what our vocals sound like’. But in a way, that was a testament to the fact that the musicality of recording can easily become secondary to the technology. Cher can actually sing, but the current generation of pop stars have been given a mandate that they don’t need to.”

He goes on to say that it’s not just the artists, but also a new generation of audio professionals who have bought into vocal tuning as a de facto standard. “There’s a whole generation of engineers who have grown up thinking that the first thing you do when you get into a recording session is fire up Pro Tools, ready to do repair work,” he said in the same published interview.

Not all engineers see it quite that way though. Josh Binder, a twenty-something engineer/programmer in Los Angeles, says: “When you’re working with a great singer whose pitch is right on, you can still apply Auto-Tune,” he says. “I’ll throw a chromatic Auto-Tune [patch] onto the vocal with a kind of mellow responsiveness level, which gives it a nice chorus/flanging effect. I’ll print the effect to a separate track and then paste it into the comped vocal mix at the end. You hear that kind of sound a lot now on female voices, like Christina Aguilera, and on a lot of really soulful R&B vocals. It’s not there to fix the vocal; it’s there to be part of the vocal sound.

“You can also use it to get a very cool portamento effect on vocals or on instruments,” Binder continues. “When you get a nice R&B slide or slur in the vocal, Auto-Tune can enhance it and make it even smoother. I mean, it almost sounds calculated, like you can hear the algorithms processing as you do it, but that has become part of the vocal sound for a lot of singers now.”

But Binder also opines that it’s not the public that drives the use of auto-tuning, nor is it a lack of chopping and comping, in most cases. Rather, he says, it’s frequently producers striving for perfection, often thinking of radio performances. “But whatever the reason someone uses it, it’s not hard to tell that it’s being used,” he says. “For people who have heard a vocal track before it’s processed and then after, the difference is pretty apparent if you have reasonably decent ears. The new trick will be finding ways to use it and not have anyone notice.”

Uk engineer Donal Hodgson says, “I don’t believe there should be any limitations on the resources used to reach a great-sounding vocal, regardless of the singer’s ability. If the vocal performance isn’t cutting it, then get the toolbox out and fix it. Having said that, on the rare occasion I have been sent into the studio with someone who can’t sing, all the Auto-Tune in the world isn’t going to make them sound like a singer! I believe some talent is needed in the first place and then all the tricks can be added. I suppose this technology could be considered either as inducing apathy, or as a time saver — I have often fixed a vocal because it was quicker and easier than sending the singer back to the booth. I think it might be human nature.”

Vocals in the mix

Compression

Dynamic control is an essential part of recording vocals. The best dynamic control is achieved from someone who knows good mic technique, getting closer for more intimate sections and moving further away when singing more forcefully. Unfortunately, few vocalists are accomplished at mic technique, so you may need to use electronic dynamics control (compression) instead. Compression and limiting are used on vocal tracks to smooth out the transients in the performance, keep the level steady, and help the vocals sit comfortably within or slightly above the other instruments in a mix. Common compression techniques for vocals usually include peak limiting, light constant compression, and squashing.

Though most engineers will apply some compression at the recording stage, modern productions tend to require the ‘in your face’ type of vocal’, so that compression has become very much an effect on vocals at the mixing stage.

As a general rule, soft-knee compressors tend to be the least obtrusive, as they will have a gentler compression curve. If you want the compression to add warmth and excitement to your sound, try an opto-compressor, valves, or a hard-knee setting with a higher ratio setting than you’d normally use. Typically the LA2 is usually one of the favourites for vocals because the attack sounds very natural. Remember what we discussed about the sound of compressors, so if you have a few available, it is worth comparing them to hear which one works best. We discussed the techniques of using compression and limiting earlier in the course, so I won’t restate them here.

A common mistake is to try to compensate for all the level changes in a vocal performance with the compressor only. Levels may vary considerably in a vocal take between verses, choruses, bridges, etc. – so that even with compression you will have to ride the fader volume of the vocals so that it always sits nicely in (or slightly above) the mix.

Sometimes, when more control is needed, you may want to use two compressors, or a limiter and a compressor – one to control the transients and the other one to compress the overall dynamic range. Be aware that compression raises the background noise (for every 1dB of gain reduction, the background noise in quiet passages will come up by 1dB), and heavy compression can also exaggerate vocal sibilance.

EQ:

We discussed in Week 1 the common practice of carving EQ holes to make room for the primary frequencies in specific tracks in a mix. Vocal intelligibility is mainly found in the 1 kHz to 4 kHz frequency range. By notching some of these middle frequencies on your guitar and keyboard tracks, you can make room for the lead vocal to cut through. You can also go one step further by boosting the vocals in this range while attenuating the same frequencies in the rest of the instrumental tracks, to make the vocals stand out while maintaining a natural overall blend.

Because everyone has a different-sounding voice, vocals are one of the most challenging “instruments” to EQ. Vocal range and gender affect the recorded track the most, but some EQing of the frequencies in the following table can help improve the sound of a vocal performance.

When you’re working with EQ on vocal tracks, it helps to keep a few things in mind:

- Not many people can hear a boost or cut of 1 dB or less when altering the EQ on a sound. In fact, most people won’t even notice a 2 dB to 3 dB change (except people like us). However, subtle changes like these are often very effective. Large changes in EQ (boosts/cuts of 9 dB or more) should be avoided in most cases, unless an extreme effect is desired.

- Instead of automatically boosting a frequency to make it stand out, always consider attenuating

a different frequency to help the intended frequency stand out. That is, try “cutting” a frequency on another track rather than boosting the track you want to emphasize. - Be aware that any EQ settings you change on a particular instrument or voice will affect not only

its sound, but also how the sound of that instrument interacts with all the other tracks in the mix. When altering EQ, don’t listen to the track in solo for too long (if at all). You may make the track sound great by itself, but it might not work with the rest of the instruments.

Also, try these additional tweaks:

- To increase brightness and/or open up the vocal sound, apply a small boost above 6 kHz (as long as it doesn’t affect the sibilance of the track).

- Treat harsh vocals by cutting some frequencies either in the 1kHz – 2kHz range or the 2.5kHz – 4kHz range to smooth out the performance.

- Fatten up the sound by accentuating the bass frequencies between 200Hz and 600Hz.

- Roll off the frequencies below 60Hz on a vocal track using a high-pass filter. This range rarely contains any useful vocal information, and can increase the track’s noise if not eliminated.

De-esser

The advantage of using the de-esser rather than an EQ to cut high frequencies is that it compresses the signal dynamically, rather than statically. This prevents the sound from becoming darker when no sibilance is present in the signal. The de-esser has extremely fast attack and release times.

When using the de-esser, you can set the frequency range being compressed (the suppressor frequency) independently of the frequency range being analyzed (the detector frequency). The two ranges can be easily compared in the de-esser’s detector and suppressor frequency range displays

The suppressor frequency range is reduced in level for as long as the Detector frequency threshold is exceeded.

The de-esser does not use a frequency-dividing network (a crossover utilizing low-pass and high-pass filters). Rather, it isolates and subtracts the frequency band, resulting in no alteration of the phase curve.

The detector parameters are on the left side of the de-esser window, and the suppressor parameters are on the right. The center section includes the detector and suppressor displays, and the smoothing slider.

Vocal Treatments

Reverb

Although we’ve seen a recent trend in an overall ‘dryer’ sound (more about that later), the use of reverb on vocals (lead and backing) is still widely used. It’s important to understand the way reverb affects the listener’s perception of a vocal line. For example, adding a lot of reverberation tends to reduce intelligibility, especially with longer decay times, and it can fill up vital space that’s needed to create contrast. Bright reverbs can also emphasise sibilance. On the other hand, too little reverb can make the vocal sound disassociated from the backing track, a bit like a ‘Karaoke’ mix.

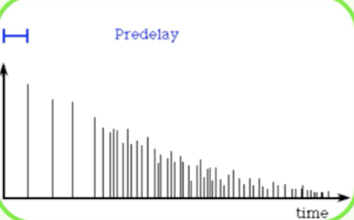

From a psychoacoustic point of view, reverb also affects the perceived position from which the vocals emanate. Adding a lot of reverb creates an impression of distance, which is directly at odds with the usual goal of placing the singer at the front of the band. To make a vocal sound up- front and intimate, you may need to use quite a short setting, but another popular trick when you need stronger and longer reverbs, is to add between 50 and 100ms of pre-delay to the reverb. In order to put a little space between the dry vocal and the reverb that follows, you might want to try inserting a delay unit before the reverb and set up the pre delay with the delay unit.

It is quite a common practice to use two reverb processors on different sends, one to provide an ambience setting to liven up the voice (ambience or room, without hearing an obvious reverb), and another one with a longer time decay (like a plate or hall). Plate reverbs are often used when longer decay times are needed.

As with instruments, long reverb decays work better in songs that leave space for them. One technique often used to prevent reverb from trampling everything is to use automation on the sends that feed the reverb(s), so you can control how much reverb is applied in different parts of the song. Typically you can have a ‘dryer’, more intimate sound for the verses and a ‘bigger’ sound in the chorus. And you can do the same with certain lines only, which you might want to emphasize. Some engineers might end up having 3 reverbs on the lead vocal, bringing them in and out in the mix.

Bright reverbs can flatter vocals but may exaggerate sibilance. If the vocal was fine before adding the reverb, an alternative to de- essing the vocals is to de-ess the feed to the reverb unit, so that sibilance is removed before the reverb is applied.

Delays

We have discussed in depth the use of delays previously, and some of its use when mixing vocals, from creating ADT (double track) to repetition of words. Shorter delays are great when you want to add a sense of space without using reverbs (try short delay times such as 1/8th or 1/16th). Multi tap delays can also be quite useful as they will avoid the obvious repetition of words.

Longer delay times c a n also compromise the comprehension, as words will overlap each other. You can use duck delays to attenuate the effect. A duck delay brings the level of delay down whilst the direct signal is playing, and brings the level of the delay up when the incoming signal stops, so that the delay is only heard in the gaps. If you don’t have a delay unit that offers this feature you can create it with a gate with a duck function such as the Drawmer DS201.

As with reverbs, engineers like to automate the delay feeds, especially with vocals. This is a very common technique so that you can select which lines or words have a delay applied. This is often used to repeat single words, to emphasize either the meaning or to fill a gap. Quite often the delay is EQ’d quite radically, filtered or processed furthered (distortion, modulations etc.)

As I have mentioned previously, it is also quite common practice to add a touch of reverb to the delay signal, so the delay blends with the rest of the track.

ADT

We also discussed this feature in previous weeks, but let us look at some more practical tips on how to create ADT:

- Use a short delay time of 10 to 35ms.

- Copy the original vocal track to another track, and move by the same amount as mentioned above.

- Harmonisers or pitch-shifters are also great to fatten up a vocal sound. If you want to double the vocal, use a mono pitch shifter, detune slightly down, around –8 cents. If you want a stereo effect, use either two mono or a stereo device and pitch one side down and the other up.

- With doubled vocals, panning both to centre, or panning one more left and one more right, gives a very different overall effect. For example, if background vocals are part of the picture, I almost always put the voice in the centre. If I want the voice to cede some of its prominence to the instruments, I’ll spread the two tracks out a little bit to decentralize the vocal.

- Use different panning for particular parts of the song. Typically the verse will feature more central and the chorus more open for a ‘bigger’ sound.

More and more software developers have released dedicated vocals effect processors that include ADT, such as Waves and Antares for example.

Check out the AVox product from Antares – it includes a plug-in for ADT called “DUO”, as well as other dedicated vocal processors.

“DUO” is an all-in-one ADT, with the possibility of altering voice timbre, pitch, time and vibrato.

Dry or Wet?

Vocal production techniques have been evolving quite rapidly over the last decade. Some engineers will tell you that, while there are now more effects on vocals, the net result has been a drier sound than vocals effected with traditional reverb, mainly because most new effects track the vocal, rather than tail it as reverb does.

“Artists say they want drier-sounding vocals,” says Michael Brauer, engineer for Coldplay, “but what they really mean is that they want something other than reverb.” When you hear the vocal truly dry, it loses its life and doesn’t quite blend with the rest of the track.

If you want a vocal really dry, try to pass the signal through different compressors, as each will have its own characteristics, to get an ‘in your face’ vocal sound. Also, adding a bit of distortion via a send and blending the signal back with the original can add some ‘urgency’ to the performance.

Everything we’ve discussed previously can apply here, including subtle pitch shifting, Leslie speaker simulation, other modulation, distortion, etc. Some engineers might use up to six harmonizers at a time on a lead vocal, blending them in lightly to give a lead vocal more emphasis.

The key to processing vocals, whatever the direction you’ll be taking, is to have the right balance. Don’t use effects just because you have them available, which is the danger nowadays with the vast range of plug-ins; they have to work musically for the track. Listening to a lot of records will help you to assess how many effects are applied, and quite often you will notice how subtle the effects on vocals are, although without them the vocal would sound “lost” in the mix.

Many o the general vocal processing rules also apply to backing vocals, except that you don’t have to strive to push the backing vocals to the front of the mix as you do with lead vocals. Indeed, backing vocals are usually designed to sit a little behind the lead vocalist. A patch with obvious early reflections will help thicken BVs, and if you need to use a longer reverb time you don’t have to worry about the backing vocals sitting too far back.

Nowadays, BVs are often associated with BIG stereo, particularly in the choruses, and that’s becoming the norm in pretty much every musical genre. It is now quite common to at least triple/quadruple, or have 5 parts for every harmony, so that if you have a four-harmony part on the bridge, for example, you’ll end up with 16 or 20 tracks of BVs. If you also have a counter melody or vocal pad (OOOOHs and AAAAHs) underneath, introducing further three-part harmonies, you have another 12 or 15 audio tracks, which is why you can end up with around 100 tracks to deal with in your final mix (a very common situation nowadays).

Submix

A technique is to create “slave reels” in your work-in-progress to help keep tracks down during the production process. The idea is that you start with your first session, which contains the music, which we’ll call “XYZ song – backing track”. Bounce all those tracks down to a stereo rough mix pair, import those two tracks into a new session named “XYZ Song Background Vocal Tracking” and leave that “master reel” untouched for the meantime. Make sure the new session has the same start time, tempo, and all pertinent session settings, and record the background vocals there.

You might end up with as many as 30 or 40 tracks of backing vocals, sometimes more if each part is tracked five times. The key here is to create stereo mixes for each harmony part, so that you can still control the level of each part in the final mix, while considerably reducing the amount of tracks to deal with. A five-part harmony, let’s say, at four tracks per note, will give you 20 tracks of vocals that you’ve now comped down to ten tracks (5 stereo pairs).

You can now import the comped BVs into the original session, and save it under another name. Now you can start mixing but can always come back to the BV tracking session if any changes need to be made.

You should do the ‘cleaning’ part at the submix stage, as once bounced into stereo pairs, it will be more difficult to clean in detail, or tune etc. (as we’ve previously discussed with lead vocals). Once you have “perfect” mixes of each part, it will be easier to bring them to sit nicely

Cleaning Tips

All the ‘cleaning’ techniques described earlier apply here too (pop, noise, tuning problems, etc.), but another important factor to consider is timing. Ideally each part should be exactly matched to each other, to get a nicely thick and slick BV effect, but sometimes you might have to adjust the timing of some of the individual parts to obtain a better blend.

One technique to tighten up the beginning and end of words is to group every desired track, inserting a gate triggered with one of the parts. Now the gate will respond to the signal of that track – very useful when some phrases ending with ‘S’ end later than others. With a DAW, you can do the same by cutting all desired audio regions and applying the same fade “IN and OUT” to all of them.

When some words are slightly out, you can cut out the word and move it slightly as needed. You might need to use crossfades between regions to avoid unpleasant clicks.

There are occasions when recorded double tracks and harmonies are just too out of time, and even moving them back and forth doesn’t solve the problem. There is software designed just for that: ‘Vocal Align’ by Synchro Arts. It’s quite widely used to tighten up any double-tracking vocals and instruments. It works well on vocals with a ‘loose’ setting (settings are 1 to 5, with 1 being very tight).

(VocALign® is an audio software solution for music and audio post that will adjust the timing of one audio signal to match the timing of another )

Panning

Panning is the one thing that can be totally different for the backing vocals than for the lead. Depending on the number of backing vocal parts, all sorts of interesting panning schemes abound. A lead vocal – the dominant element in the mix – is almost always panned to the centre, so I rarely if ever pan a backing vocal centre. Think of it as a stage – few lead singers would like their backing vocalists to breathe down their necks.

And in fact, both in terms of sonic intelligibility and interest, it makes sense to give each its own unique space. So, keeping in mind the rest of the sounds in the mix, I try to find a unique pan position for the backing vocal – one that isn’t distracting if the part shouldn’t call attention to itself, and that stands out if the part should call attention to itself.

We can’t cover every possible situation. For now, let’s go with a lead vocal, one backing vocal that harmonizes the lead vocal, and two different two-part sections, each of which harmonizes a unique contrapuntal part. First, I would almost certainly place the lead vocal dead centre. I’d find a unique, non-centre pan for the harmony vocal, then I’d experiment with how it sounds to group each of the two- part counterpoints where the “A” part is mostly to one side and the “B” part is mostly to the other. Then I’d try to put one “A” part on each side, and one ”B” part on each side.

In either of these two cases, I would always give each backing vocal track its own unique pan position. For instance, in the case where the two “A” parts are on the same side, I might begin with one of the two at 60% left and the other at 35% left. Conversely, I’d place the two “B” parts on the right, mirroring these settings— one at 35% right, the other at 60% right. Based on the sound of these possible configurations, I would then decide how to proceed. The exact pan of each of these parts would be subject to the taste of the mixer, producer and artist. I may set the backing vocals one way, live with it while working on other things, and change it up later.

Now that you have your submixes of BVs (for example: low, mid and high harmony chorus, in 3 stereo pairs), I would advise you to send them to a group, so you can control this part with one fader but still adjust the level for each harmony part, as well as the level of reverb or other effects you’ve applied. If you have other blocks of harmonies, do the same, so that you end up with stereo mixes for each part, such as BVs CHORUS, BVs BRIDGE, BVs OUTRO. What started with 50 tracks of backing vocals is now reduced to 3 stereo pairs.

A very important issue when dealing with a lot of harmonies is the balance. Spend some time trying different levels for each part, until it blends really nicely. Usually you should have one part dominating the others – normally the main melody – and the other harmonies slightly underneath.

I find that EQ and compression should sometimes only be used on the overall group (i.e. CHORUS BVs), rather than on individual parts. It’s quite common practice to add a bit of top end at this stage to add some air to the overall sound. Exciters used in moderation can work brilliantly in this situation.