The Vocoder

The Vocoder

A Vocoder – name derived from voice coder, formerly also called Voder – is a speech analyser and synthesizer.

A Vocoder – name derived from voice coder, formerly also called Voder – is a speech analyser and synthesizer. It was originally developed as a speech coder for telecommunications applications in the 1930s, the idea being to code speech for transmission. Its primary use in this fashion was for secure radio communication, where voice the had to be digitized, encrypted and then transmitted on a narrow, voice-bandwidth channel.

The human voice consists of sounds generated by the opening and closing of the glottis by the vocal cords, which produces a periodic waveform with many harmonics. This basic sound is then filtered by the nose and throat (a complicated resonant piping system) to produce differences in harmonic content (formants) in a controlled way, creating the wide variety of sounds used in speech. There is another set of sounds, known as the unvoiced and plosive sounds, which are created or modified by the mouth in different fashions.

The vocoder examines speech by measuring how its spectral characteristics change over time. This results in a series of numbers representing these modified frequencies at any particular time as the user speaks. In simple terms, the signal is split into a number of frequency bands (the larger this number, the more accurate the analysis) and the level of signal present at each frequency band gives the instantaneous representation of the spectral energy content. Thus the vocoder dramatically reduces the amount of information needed to store speech, from a complete recording to a series of numbers. To recreate speech, the vocoder simply reverses the process, processing a broadband noise source by passing it through a stage that filters the frequency content based on the originally recorded series of numbers. Information about the instantaneous frequency (as distinct from the spectral characteristic) of the original voice signal is discarded, as it wasn’t important to preserve this for the purposes of the vocoder’s original use as an encryption aid. It is this “dehumanizing” quality of the vocoding process that has made it useful in creating special voice effects in popular music and audio entertainment.

In 1970 Wendy Carlos and Robert Moog built another musical vocoder, a 10-band device inspired by the vocoder designs of Homer Dudley. It was originally called a spectrum encoder-decoder, and later referred to simply as a vocoder. The carrier signal came from a Moog modular synthesizer, and the modulator from a microphone input. The output of the 10-band vocoder was fairly intelligible, but relied on specially articulated speech. Later, improved vocoders use a high-pass filter to let some sibilance through from the microphone. This ruined the device for its original speech-coding application, but it made the “talking synthesizer” effect much more intelligible.

In 1970 Wendy Carlos and Robert Moog built another musical vocoder, a 10-band device inspired by the vocoder designs of Homer Dudley. It was originally called a spectrum encoder-decoder, and later referred to simply as a vocoder. The carrier signal came from a Moog modular synthesizer, and the modulator from a microphone input. The output of the 10-band vocoder was fairly intelligible, but relied on specially articulated speech. Later, improved vocoders use a high-pass filter to let some sibilance through from the microphone. This ruined the device for its original speech-coding application, but it made the “talking synthesizer” effect much more intelligible.

Carlos and Moog’s vocoder was featured in several recordings, including the soundtrack to Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange in which the vocoder sang the vocal part of Beethoven’s “Ninth Symphony”. Also featured in the soundtrack was a piece called “Timesteps,” which featured the vocoder in two sections. “Timesteps” was originally intended as merely an introduction to vocoders for the “timid listener”, but Kubrick chose to include the piece on the soundtrack, much to the surprise of Wendy Carlos.

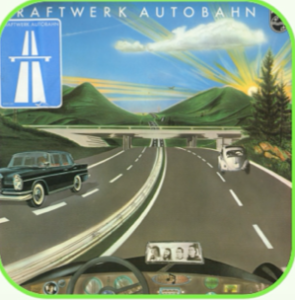

Kraftwerk’s Autobahn (1974) was the first successful pop/rock album to feature vocoder vocals. Another of the early songs to feature a vocoder was “The Raven” on the 1976 album Tales of Mystery and Imagination by progressive rock band The Alan Parsons Project. The vocoder was also used on later albums such as I Robot. Following Alan Parsons’ example, vocoders began to appear in pop music in the late 1970s, for example, on disco recordings. Jeff Lynne of Electric Light Orchestra used the vocoder on several albums such as Time (featuring the Roland VP-330 Plus MkI). ELO songs such as “Mr. Blue Sky” and “Sweet Talkin’ Woman” both from Out of the Blue (1977) use the vocoder extensively. Featured on the album is the EMS Vocoder 2000W MkI, and the EMS Vocoder (-System) 2000 (W or B, MkI or II).

Vocoders have appeared on pop recordings from time to time ever since, most often simply as a special effect rather than a featured aspect of the work. However, many experimental electronic artists of the New Age music genre often utilize vocoders in a more comprehensive manner in specific works, such as Jean Michel Jarre (on Zoolook, 1984) and Mike Oldfield (on Five Miles Out, 1982). There are also some artists who have made vocoders an essential part of their music, either overall or during an extended phase. Examples include the German synthpop group Kraftwerk, Stevie Wonder – “Send One Your Love”, “A Seed’s a Star” – and jazz/fusion keyboardist Herbie Hancock during his late 1970s period.

Vocoders have appeared on pop recordings from time to time ever since, most often simply as a special effect rather than a featured aspect of the work. However, many experimental electronic artists of the New Age music genre often utilize vocoders in a more comprehensive manner in specific works, such as Jean Michel Jarre (on Zoolook, 1984) and Mike Oldfield (on Five Miles Out, 1982). There are also some artists who have made vocoders an essential part of their music, either overall or during an extended phase. Examples include the German synthpop group Kraftwerk, Stevie Wonder – “Send One Your Love”, “A Seed’s a Star” – and jazz/fusion keyboardist Herbie Hancock during his late 1970s period.

At one time vocoders were considered quite esoteric, but nowadays they come built into some multi-effects units. Less costly stand-alone units are also fairly common. On top of that, there are some very effective vocoder plug-ins that can be used within sequencers.

Carrier and Modulator

A vocoder requires two inputs to generate an output: a “carrier” and a “modulator”. It analyzes the modulator signal, applies its frequency characteristics to the carrier signal and outputs the resulting “modulated” carrier signal. In the most typical case, the carrier signal is a string or pad sound and the modulator signal is speech or vocals – the result will be a talking or singing synth sound. The modulator could also be drums or percussion (for rhythmically modulated sounds and effects) or any sound with changing frequency content.

Filter bands

Essentially, the vocoder superimposes the frequency spectrum of one sound (the modulator) on the second sound (the carrier). The way this is achieved is that the frequency spectrum of the modulator is continually monitored using a bank of frequency-spaced band-pass filters, and the information is used to control the gains of a corresponding bank of band-pass filters in the carrier’s signal path. Thus, as the spectrum of the modulator changes, the carrier’s filter bank settings follow it. If a voice is used as the modulator and a harmonically rich musical sound as the carrier, this results in the classic vocoder sound – the voice seems to take on the pitch and timbre of the carrier sound, but the vocal articulation is still recognizable because of the dynamic action of the filter bank following the continually

changing spectrum of the voice. As you might imagine, the more filter bands the vocoder has, the more accurate and intelligible the speech-like element of the output signal.

Essentially, the vocoder superimposes the frequency spectrum of one sound (the modulator) on the second sound (the carrier). The way this is achieved is that the frequency spectrum of the modulator is continually monitored using a bank of frequency-spaced band-pass filters, and the information is used to control the gains of a corresponding bank of band-pass filters in the carrier’s signal path. Thus, as the spectrum of the modulator changes, the carrier’s filter bank settings follow it. If a voice is used as the modulator and a harmonically rich musical sound as the carrier, this results in the classic vocoder sound – the voice seems to take on the pitch and timbre of the carrier sound, but the vocal articulation is still recognizable because of the dynamic action of the filter bank following the continually

changing spectrum of the voice. As you might imagine, the more filter bands the vocoder has, the more accurate and intelligible the speech-like element of the output signal.

In Practice

It is apparent from this description of the vocoding process that you need signals arriving at both inputs simultaneously before you can obtain an output signal. It can also be helpful to compress both inputs to the vocoder in order to keep the output levels stable. On the other hand, if the modulation input is a voice, you might find that the vocoder is triggered undesirably by breath noises, in which case a gate inserted between the microphone and the vocoder’s input will also be an improvement.

The talking synth effect has been used on countless records (for example, ‘Blue Monday’ by New Order, ‘Mr Blue Sky’ by ELO and ‘Rocket’ by Herbie Hancock), but this isn’t the only way to use a vocoder. By substituting the vocal input with a recording of background noise in the local pub, and by vocoding this with a rich synth pad, you can create a very organic pad sound with a lot of movement. Similarly, two different synth sounds or samples can be vocoded together to create a totally new sound. If the modulator signal includes dramatic changes, such as a filter sweep, these will be imposed on the carrier. The real key is to experiment, but a point to keep in mind is that – because the end result is created subtractively – the carrier signal needs to be harmonically rich in order to give the filters something to work on. If the carrier is a synth sound, an open filter setting combined with a sawtooth or pulse wave works well.

When vocoders were first developed, it was realised that, whilst the pitched elements of vocal sounds provided a good modulation source, vocal components such as ‘S’, ‘F’ and ‘T’ sounds tended to get lost so that vocal clarity suffered. Different strategies were devised to help with the intelligibility of vocoded speech. One of these was to replace some of the consonant sounds with bursts of noise, but a far simpler method was to add a low-pass filtered version of the vocal input into the output. The latter method works well, because the higher-frequency region of the vocal spectrum contains most of the energy of many vocal consonants, yet without many pitched components. By filtering out everything below 5 kHz or so, then adding the remaining high frequencies to the vocoded signal, vocal intelligibility can be improved enormously.

Integrating Within the Mix

- Feed one aux send to a vocoder carrier input, and another send to the vocoder’s modulation input. Note that this requires a real vocoder with two inputs, not one of the digital simulations that have only one input (and perhaps an additional input for MIDI control). This allows any signal to modulate any other signal, which can provide a very cool effect if you take something percussive as the modulator input and use it to trigger a more sustained part, such as bass or long piano chords.

- Use a drum pattern to create some interesting rhythmical pads. Vocoded drums can be a great starting point to write electronic music – you just need a drum loop, a synth and a vocoder.

There are numerous plug-ins available, such as the Orange vocoder by Prosoniq, MDA talkbox and vocoder (this supports 2 inputs like real hardware, useful), Vokator, and many others.