Mixing Electronic Music

The Noise Gate

Some of you may be aware that the primary use for a gate is to reduce noise and any unwanted signal that is present in your recordings. For example you may have a vocal take with rumble, computer noise or heavy breathing in- between phrases. A gate is the perfect tool for removing these problem areas, often with zero impact on the parts you want to keep.

As a gate is really just an automated level control, they use very little to no CPU power. Most DAWs include one or even two gates as standard and these will often be bundled with a number of pre-sets to get you going.

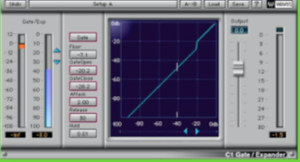

(Waves C1 Gate/Expander)

As the process of gating isn’t particularly exciting and is often seen as purely a problem-solving exercise, the gate can be somewhat overlooked as a creative effect.

First up let’s take a look at using our gates in an almost traditional way, but instead of reducing, we’ll try using it in a similar way to a transient designer. This basically means that we can actually remove parts of a drum track or loop. This can be really useful for cleaning up our overall sound.

Choose a loop with a fair bit of noise present. This technique can quite easily be applied to a drum group / buss and will work equally well on acoustic drums as it does on electronic sounds.

Initialise the plug-in so that no gating takes place and no signal can be heard, this is a good starting point and is often the best way to go when using dynamics processors in general.

Although we can filter out many of the sounds in the loop, to make the remaining sounds a little more realistic we have to alter the release and hold times. When doing this, try to mimic the actual release times of the drum sounds themselves. In doing this you may get

some ‘bleed’ from the other sounds in the loop but this is to be expected and shouldn’t be too obvious in the mix.

When comparing the before and after you should hear a dramatic change in the loop. Using this technique, you can slightly clean up your drum parts or completely transform them depending on the intensity of your settings.

Gated Reverbs

Most fully featured, modern reverb plug-ins will contain some kind of gated reverb effect and they can work really well on short percussive sounds or drums. Although these presets can work well, you can gain much more control over this effect if you can create it using your own processors.

You can hear that in their dry form many snare sounds are not particularly interesting. By adding a gated reverb we can make many a lot more useable.

At this point you’ll want to play with the reverb mix, gate release and gain reduction amount. This will allow you to match the reverb time to the snare’s release and also ensure there are no unwanted clicks and pops introduced by the gating.

Rhythmical Gating and Gated Patterns

One of the most creative ways to use your gate plug-ins is to produce rhythmical patterns with them. As a lot of DAWs now feature native side chaining, you can now feed your gate with just about any signal you like. This allows you to use the gate as a sort of automated tremolo or pattern generator. Some really excellent results can be achieved with a little imagination.

The gate is placed on an instrument loop and the percussion loop is set to control the side chain circuit. This will allow us to use the peaks of the percussion pattern to activate the gating effect.

Once this configuration is set up, start to bring the threshold of the gate down until you hear some gating occur.

Once the gating is taking place try sending the percussion to loop to ‘no output’ or a muted group. You should now hear the instrument loop with only the gated effect. This will allow you to make more exact adjustments to the gate’s settings.

Of course you can always leave the percussion loop out of the mix and just use it as a trigger. If you prefer, you can program your own trigger part using MIDI, this will allow a more personalized pattern to be produced.

Creative and Alternative Uses for Side-chaining

Many people use side-chaining as a way to make their tracks pump in time with their kick drum or to lower the level of music when a voice is present, but there is so much more we can do with the process. So let’s get into it and see what can be achieved.

Using side chain based compression is a great way to make your drum parts a little more dynamic and interesting. You can also use this method to create more realistic clutch and choke effects.

Let’s say you have a running 16th high-hat pattern, this maybe programmed or it could be a loop and you want to introduce some open high-hat elements to the pattern. These extra hat sounds can often get lost in an already busy sequence or loop, of course you could go through removing the closed hats manually from the original sequence to create space, but side-chaining can offer a better solution.

By using a side-chain capable compressor on the original closed hat pattern and routing the new open hats to the key input, the closed hats ‘duck’ every time the new hat sound plays. This not only gives the open hat sound the space it deserves but also gives you a very organic sound, something that is very difficult to achieve with programming alone.

With the routing set up you should start to hear the original hat line ducking when the open hat appears. It’s now just a case of deciding how much reduction you want to occur and fine tuning the release time to match your project’s tempo.

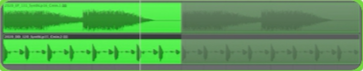

(The compressor with tweaked settings in action)

Try using a snare or percussion sound for a fill or variation during a transition in your arrangement.

Then apply a side chain compressor to the rest of your drums and percussion. The new snare fill will cut right through the mix, and the effect will create an aggressive feel.

Cleaner Effects

When using any effect with a tail (i.e. reverb, echo or delay) there is always a danger of muddying a good mix. There are times when a really large reverb or delay are called for and with the use of side chain compression we can generally use these larger-than- life effects, without detrimentally effecting our mix.

To use this technique we first need to set up a send / return routing. The compressor is then placed on the return channel or buss. The key input for this compressor can be any element in your mix, traditionally the kick drum or drum group would be used but things get a little more interesting if alternative sources are used.

Try using the actual signal that you are affecting as the key input. For example, if you are affecting a guitar solo you can try using this to cause the ducking on your effects bus. This will allow your guitar to pass through the dense effect without being too confused. When the part stops the effects buss level will rise allowing you to hear the reverb or delay you are using.

This technique is great for lead lines, guitar solos and generally anything monophonic in nature. Real definition can be added to parts even when very intense effects are being applied. Also experiment with using other random elements from your mix as the key input on the effects buss. Sometimes the results can be quite surprising.

If you are producing electronic music with a number of different synth lines, or rock music with multiple guitar parts, it’s likely that these instruments can be fighting for space. Ducking can be used to create spaces for these sounds to live in and enable them to be in the mix at the same time.

Marrying Synth and Guitar Parts

If you are producing electronic music with a number of different synth lines, or rock music with multiple guitar parts, it’s likely that these instruments can be fighting for space. Ducking can be used to create spaces for these sounds to live in and enable them to be in the mix at the same time.

Simply choose one of the sounds as the one that will be compressed and another that will act as the key input. It’s a good idea to use a sound that is only used for small bursts as the key input, this way your ‘main sound’ will be ducked when it appear.

The same effect can be used to duck a rhythm guitar or pad sound when a more prominent lead is playing. Again it’s all about control and making space. These methods can really lead to a cleaner more intelligible mix.

Pre- and Post-fader

A common question is whether or not to send tracks to an effects send using pre-fader or post-fader. Most DAWs will let you route to an effects send using either pre or post. When an Aux send is configured post-fader, the effect’s wet-to-dry ratio is preserved as you raise and lower the dry channel fader. So lowering a channel’s fader simultaneously lowers the Aux send signal level. That keeps you from having to adjust effects return fader levels in the mixer or wet/dry ratios at the effects processor every time you make a level adjustment with a track’s channel fader.

In most cases, you’ll want to keep the balance between a dry track and its effects relatively constant throughout the mixdown process, so post-fader effect sends are used more often than pre-fader effect sends.

However, there are some interesting uses for the pre-fader setting, for example creating an effect such as a sound disappearing into expansive reverb. A good example of this is when you hear someone in a film walking and the steps emerge out of a distant reverberant sound, come closer and more present as they “approach” you, and then return to the distant echo as they walk away. This is done using a blend of the original and effects channels and changing their levels independently of each other using the ‘pre’ setting.

As its name suggests, a pre-fader send is not influenced by the dry channel-fader moving, because the signal is sent to the processor through the Aux send before it gets to the dry channel fader. Therefore, the processed signal level from a pre-fader Aux send remains constant, no matter how you move its corresponding dry channel fader.

So, in the case of the “footsteps” example mentioned above, this is achieved by keeping the effect send reverb level constant while you slowly increase its dry level (giving the sense that the person is “approaching”) and then returning it to a low level (giving the impression that they are walking away).

Upward Compression

As with any art form, advanced techniques develop out of need and the want to get a better sounding record. The sound of compression is now on nearly every music recording we hear. The subtle distortion the non-linear circuit of compressors, limiters and levelling amplifiers offers is pleasant to the ear.

(The Crane Song STC-8)

The downside is that with the most common form of compression, downward compression has an increased level of distortion which may negatively affect a single sound or groups of sound, hazing over the programs clarity, clamping down on the dynamic range of the song and ultimately robbing the song of feel, punch and drive. This takes away from the natural dynamics and excitement of the music.

A method to preserve the dynamic range and add punch and character to the program is upward compression. As opposed to downward compression, upward compression increases the loudness of low level sounds without the pushing louder passages down. For example, it can amplify the dirty hissing noise of a drum loop.

The way we do this is to sum the source audio with the compressor’s output signal. The result is free from the negative side effects of 100% non-linear compression.

Upward compression can be achieved by transparent parallel compression, which you learnt about earlier in the course. Upward compression adds more depth and separation to the mix and/or master. It also has an aggressive side, lending an attitude to the music. Upward compression can beef-up lows, make clear and punchy mids and preserve the dynamics of high frequency information as well.

If you think about it, parallel compression is adding more frequencies to the sum of the originating source. The ‘crushed’ (to a greater or lesser extent) sound of the compressed signal has had the transient sounds squashed, resulting in the bulk of the signal (that below the threshold) becoming ‘louder’. You do not always need to have your compressor set to punishing levels. And mixing this signal with the original source means that you are mixing in extra (near-identical) sound below the threshold of the compressor – increasing the volume…

Bear in mind also that today more and more plug-in compressors have a wet/dry control so that there isn’t always a need to set up a separate channel to experiment with this technique.

(The A-Designs HM2 Nail Compressor/Limiter)

It does not go without saying that upward compression is like any other technique. Learn it well and apply when necessary because, like all audio processes, abuse or overuse makes it unexciting. But if done properly this technique yields excellent results. Enjoy!

Setup of a studio

When connecting MIDI instruments to a computer, the most important component you’ll need is the MIDI interface. This is what will allow MIDI to be understood and transmitted into and out of your computer.

Most MIDI Interfaces are single-unit rackmount devices that connect to your computer’s USB port. They have multiple in/outs for up to 10 or more MIDI instruments.

(The ESI M8U XL – an 8in/8out MIDI Interface)

The connections are quite simple here. The computer is hooked up to the MIDI interface. The MIDI ‘outs’ from your synths go into the interface. And the MIDI ‘outs’ from the interface return to the corresponding synths. This type of set- up allows for extremely flexible control via your computer and the interface. For writing, sequencing, storing and creating patches as well as music. Also for live performance, and for stacking, controlling and programming MIDI instruments – this is by far the most common and easiest set-up.

(A Kenton MIDI to CV converter)

In order to MIDI-up your old analogue synths you will need a MIDI-to-CV/Gate converter. These devices translate MIDI data into control voltage (CV). This allows you to play your analogue synths and in many cases edit filter and envelope parameters from a MIDI controller. It is simply connected to your MIDI interface as if it were another MIDI synth itself. Be sure to configure the Converter to transmit the proper form of CV/Gate for your brand of synthesizer.

Classic Synths

Roland Juno-106

The Roland Juno-106 was a hybrid digital/analogue polyphonic synth manufactured by Roland Corporation in 1984. It featured digitally controlled oscillators (DCOs) for tuning stability and digital envelope generation along with analogue filters and signal path.

It was relatively simple in terms of its synthesis architecture. The central tone-generating component of the instrument is a set of 6 digitally controlled oscillators capable of producing sawtooth and square/pulse waveforms. The Juno is well known for its -24dB/octave analogue low-pass filter with adjustable resonance, which has been said to provide the Juno 106 with its rather distinctive sound when combined with the tone of the MC5534 wave generation modules.

The Juno-106 was the third in the Juno series of digital/analogue synthesizers. Its predecessors, the Roland Juno-6 and Roland Juno-60, were somewhat different in appearance than their later sibling, but shared most of the internal components and features in common, with the exception of a trade-off between a simple up/down arpeggiator on the earlier models and a portamento feature on the Juno-106. The Juno-106 also featured MIDI for inter-instrument communication rather than the proprietary Roland Digital Control Bus (DCB) found on earlier models. The Juno-106 is a unique synthesizer largely because it came at a time when digital synthesizer components were just being introduced, MIDI being the most important. It featured the best of the analogue and digital worlds.

Korg Mono/Poly

The Korg Mono/Poly is a “mono-polyphonic” analogue synthesizer manufactured by Korg from 1981 to 1984. This keyboard is the sister synth to the Korg Polysix.

Features include 4 VCOs with tuning, footage (16, 8, 4, 2), waveshape (triangle, saw, pulse-width, and pulse-width modulated), and amplitude. The first oscillator is the master oscillator as far as fine tuning goes. Two direct modifiers to the VCOs are a portamento control that only affects oscillators 2-4, and a pulse-width control.

There is an ‘effects’ section which includes an amplitude modulator (X-MOD) with hard-sync control, and a frequency modulator with which the frequency of the modulator can be altered by the VCF envelope or MG1. For both modulators there is the option of single modulation of all oscillators, or two carriers, and two modulators (using the VCOs).

This synth wasn’t so much designed to be a polysynth like its sister the Polysix (which was manufactured at the same time), but more of an experimental synth with gobs of modulation capabilities and different footages and wave shapes per oscillator.

Major artists known to use the Mono/Poly include: Vince Clarke of Depeche Mode, The Chemical Brothers, Chromeo, The Orb and MGMT (who cite it as their favourite synthesizer).

The Minimoog

The Minimoog was designed in response to the use of synthesizers in rock and pop music. Large modular synthesizers were expensive, cumbersome, and delicate, and not ideal for live performance. The Minimoog was designed to include the most important parts of a modular synthesizer in a compact package, without the need for patch cords. It later surpassed this original purpose, however, and became a distinctive and popular instrument in its own right. It remains in demand today, nearly four decades after its introduction, for its intuitive design and powerful bass and lead sounds.

The Minimoog is monophonic (only one note can be played at a time) and its three-oscillator design gave it its famous fat sound. The signals are routed through the Mixer to the VCF where harmonic content can be modified and resonance added. The filtered signal is then routed to the Voltage Controlled Amplifer (VCA), where its contour is shaped by a dedicated A D S (Attack, Decay/Release, Sustain) envelope generator.

Keith Emerson was the first musician to tour with a Minimoog, in 1970, during Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s ‘Pictures at an Exhibition’ shows. Many essential pitch-bending techniques were first demonstrated by him, and many keyboardists learned how to pitch-bend by following his example.